Allocating a per-capita-emission budget and utilising the countries’ comparative advantage will bring equity and sustainability.

Based on 58 indicators (increased from 40 in 2022), 11 issues, and three policy objectives, the environmental performance index (EPI) 2024 places India at a dismal 176th rank out of 180 countries. The three policy objectives with different weights assigned—environmental health (25%), ecosystem vitality (45%), and climate change (30%)—address climate change mitigation, biodiversity and habitat, forests, fisheries, air pollution, agriculture, water resources, air quality, sanitation and drinking water, heavy metals, and waste management, which are key to sustainability. The eight regions covered in the analysis show wide variation. An empirical analysis suggests that wealth and EPI scores are correlated, although there are diminishing returns subsequently. The other significant determinants of high EPI are (i) human development index (HDI) and (ii) quality of governance comprising rule of law, governance effectiveness, and control of corruption.

EPI 2024 finds only five countries—Estonia, Finland, Greece, Timor-Leste, and the United Kingdom (UK)—reducing their greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions in consonance with the target of net zero by 2050. Alarmingly, except UK, all the countries identified in EPI 2022 as “on track to reach net-zero by 2050” have since fallen off-track. The largest world economy, the United States’s (US) emissions are falling slowly and that of China, India, and Russia are increasing. Region-wise, Europe has the highest EPI scores, whereas South and Southeast Asia have the lowest. Moreover, within-region variability in EPI scores is stark. On climate change, in sub-Saharan Africa, Zimbabwe ranks 28th and Mali at 179thplace, globally. Even the high-ranking West performs poorly on the forest landscape integrity index. In terms of ecosystem vitality, Bhutan is ranked the top in southern Asia, with more than 50% of its land comprising protected areas. It also leads the world in forest conservation and sustainable management.

Botswana from sub-Saharan Africa leads the world in biodiversity and habitat indicators in EPI 2024 with protected area covering 29% of its territory. Despite the lack of protection for some key biodiversity areas, its species and ecosystem are generally well conserved, reflected in the high species habitat index and red list index. India’s position at the lowest in terms of biodiversity and habitat rankings is attributable to restricted public access to over 95% of the protected-area data submitted to the World Database on Protected Areas.

The indicators, constructed as indices, reflect their growth rate in the last decade, which poses two fundamental issues: first, when a country with very high initial emissions reduces them, its rank goes up. Likewise, when countries with low forest cover increased it over the decade, their score improved, whereas heavily forested regions could not add much, thus no reward for them. Hence, the rank and the absolute volume/performance of the indicator are not directly related but tied to their own past decade-old values. Second, the quality or productivity of the ecosystem services has not been accounted for in EPI. Old-growth tropical forests that have a much higher ecosystem value are treated at par with the new growth forests, grown as part of afforestation/reforestation efforts, which fails to foresee tragedies like the Wayanad landslide in this week.

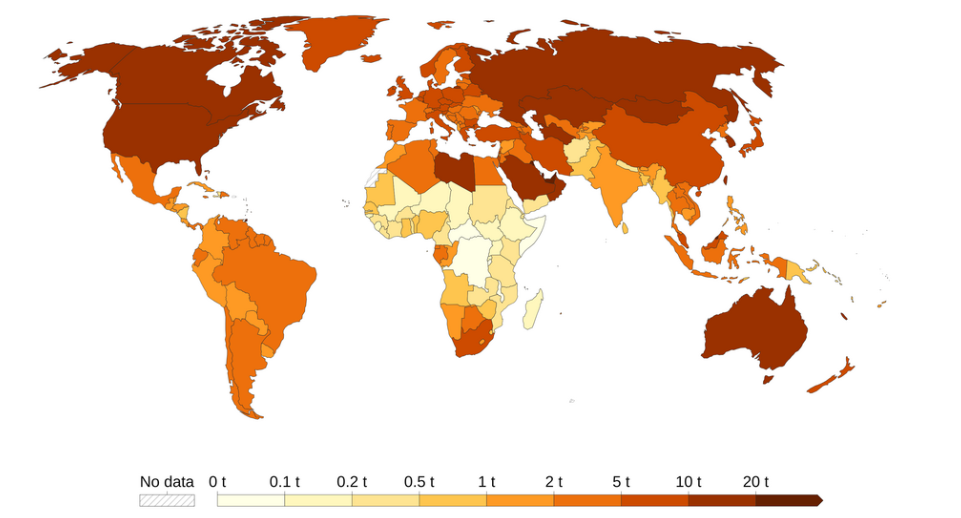

EPI 2024 introduces CO2 emission growth rates with country-specific targets as pilot indicators, although with low weightages. It allocates a carbon budget following an equal-per-capita approach. On this basis, the US’s GHG emissions are 80% higher than China and six times more than India’s, that too when it had already peaked its emissions in 2007. This justifies and calls for a greater role of historical emitters in climate finance and more carbon budget for late-developing low- and middle-income countries. The unavailability of clean energy for almost 57% of rural households in India that depend on solid fuels for cooking and lighting underscores the uneven distribution of energy consumption, which also contributes to 20%–50% of PM2.5 pollution.

With the inclusion of these and more pilot indicators as full-fledged indicators, the future editions of EPI will likely be sustainable and ensure climate justice. For instance, in China, despite reduction in air pollution, the mortality related to poor air quality has shot up due to a huge ageing and vulnerable population. Though the EPI score considers age-standardised disability-adjusted life years, it does not account for the quality of healthcare available for a country or the prevalence of comorbidities which can be taken as a pilot indicator in EPI 2026.

While still much below the target of the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (30×30 goal), there is considerable progress observed in EPI 2024; 28 countries and territories, primarily from Europe and Africa, have already protected more than 30% of their land. Additionally, seven countries have implemented protected areas in more than 30% of their exclusive economic zones. However, the Asian countries are lagging far behind. Interestingly, countries’ fishery output and their performance in the EPI 2024 fisheries indicator are uncorrelated pointing towards the scope of sustainable fishery by adopting small-scale fishing and avoiding bottom-trawling.

EPI 2024 analyses find that, in 23 countries, more than 10% of protected land is covered by cropland and buildings, whereas in 35 countries, more fishing effort in marine protected areas is observed than in unprotected areas. Protected areas in Africa face more deforestation than unprotected areas. Across the tropics, there is a lack of rangers and other personnel to enforce protection and proper management. Similarly, marine protected areas cover 30% of the territorial waters in Europe, which faces the most intensive trawling. Basically, political pressure and lobbying prevent complete implementation of “protected area norms” adding to the degradation of the planet.

Despite regulations for heavy-polluting industries, burning of agricultural residues and coal-fired power plants, their enforcement is weak and ineffective. Cutting down on GHG emissions from fossil fuel-based thermal power plants requires heavy reliance on hydroelectric, wind, and solar energy. However, offshore wind projects add pressure on coastal areas. Similarly, on land, hydropower, wind, and photovoltaic projects can significantly deplete or degrade important biodiversity areas. To reduce pressure on land mining, deep sea mining, which has been suggested as an alternative, can damage the pristine oceanic ecosystem. Thus, there are trade-offs to be made and priorities to be set based on the principle of justice. So far, the per capita emission approach appears to be the most equitable way to secure “everyone’s need, but not everyone’s greed.”